Inspired by the achievements of microwave wireless charging and microwave weapons, people have envisioned building solar power stations in space, converting solar energy into electricity, then converting it into microwaves, and transmitting these microwaves to ground receiving stations to obtain continuous electricity. The idea of a space solar power station is tempting: the efficiency of converting solar energy into electricity in space is extremely high; using microwaves to transport electricity from space to the ground is rapid and minimally affected by the atmosphere and clouds; the power generation of a space solar power station can match that of a large nuclear power plant; and this technology can provide clean energy to the ground 24 hours a day. Now, Europe, the United States, Japan, and China are all working hard to build space solar power stations, and people are looking forward to the model's success. What are the key technical challenges in building a space power station? What other difficulties exist?

In selecting the orbit for the space solar power station, multiple factors need to be considered comprehensively. Firstly, the height of the space station must be between 100 and 1500 kilometers above the ground. The closer the station is to the ground, the greater the atmospheric resistance, requiring more fuel to maintain height; if the distance is too far, high-altitude radiation increases, and round-trip costs rise. The Chinese space station has chosen an orbital altitude of 400 kilometers, balancing launch costs, operation and maintenance costs, scientific experiment needs, astronaut health, and equipment safety. Even at this altitude, the space station drops about 100 meters daily and needs its own power to maintain altitude and avoid danger, consuming 4 tons of fuel annually.

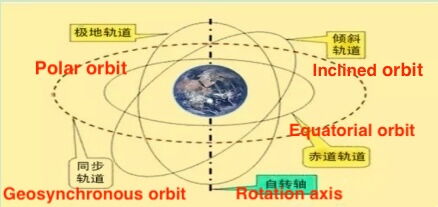

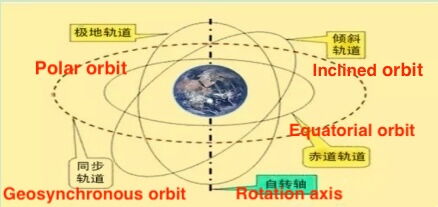

Artificial earth satellites are categorized into low orbits (<1000 kilometers), medium and high orbits (1000-20000 kilometers), and high orbits (>20000 kilometers) based on their altitude. Satellites are affected by air resistance, solar wind, light pressure, etc., during operation and may deviate from their orbits; thus, some satellites need power to maintain their orbits. If scientific experimental satellites do not need precise orbit maintenance, they can be engine-less and fall by themselves after a few years.

Synchronous satellites are satellites with an orbital altitude of 35786 kilometers, matching the Earth's rotation cycle. This type of satellite appears stationary from the ground, called a geostationary orbit satellite, a special case of the geosynchronous orbit. There is only one geostationary orbit, located in a circular orbit above the equator. Geostationary orbit satellites are suitable for communication and signal forwarding, and are most suitable for space solar power stations because the ground antenna is fixed and does not need tracking. The launch process of a geostationary orbit satellite includes using first and second-stage rockets to send the satellite into a low-Earth orbit of 200-400 kilometers, stabilizing it, then using a third-stage rocket to send it into a near-geostationary orbit, and finally using its power device to adjust it to the geostationary orbit and set the satellite's attitude.

There may be multiple deflection angles between the synchronous orbit and the Earth's equator.

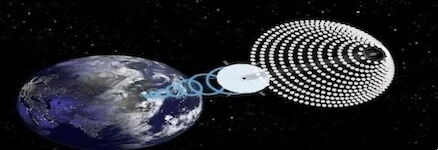

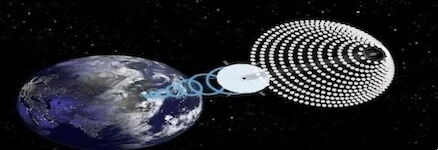

If the estimated power generation capacity of a space solar power station is one gigawatt, it is equivalent to that of a large nuclear power station. Since the intensity of sunlight in space is 5-10 times greater than on the ground, and the photoelectric conversion rate is 50%, it can be calculated that the area of the space solar panel is about 2 square kilometers. Additionally, a "microwave array launch device" and other equipment are necessary, making the space solar power station a huge structure. This massive structure can be divided into "functional components" on the ground. A "reciprocating spacecraft" and dozens of launches are required to send the functional components to geostationary orbit. It also needs to be assembled and integrated by a robot, with all the

photovoltaic panels automatically unfolding like an umbrella, and finally adjusting its position. In summary, installing a space solar power station is a very arduous task. The "space solar power station model" envisioned by scientists and engineers is as follows:

The envisioned structural diagram of the space solar power station

Can the space solar power station generate electricity 24 hours a day? This question is equivalent to asking whether there is sunlight shining on the geostationary synchronous satellite at night, or whether people can see the geostationary synchronous satellite at night. The answer is yes.

When high-energy microwaves are transmitted from space to the ground, will the loss in the atmosphere be significant? Generally, the answer is yes. The lower the frequency of the electromagnetic wave, the less the loss in the atmosphere. The frequency of sunlight is very high, resulting in significant loss in the atmosphere. The frequency of microwaves is much lower than that of sunlight, allowing them to pass through the ionosphere. The loss of microwave energy in the atmosphere is minimal. Will transmitting high-energy microwaves from space to the ground harm the environment? The primary factor affecting the environment is microwave energy rather than microwave frequency. Microwave energy transmission is safe and harmless to the environment only when the receiving capacity is controlled at a level that does not harm organisms.

It is theoretically feasible to build a space solar power station, but its implementation requires specific technical parameters at many stages. This is a large project with high technological demands, which is both attractive and expensive. Now, China has also started research on the construction of a space solar power station. China's experimental base is in Bishan, Chongqing. It is necessary to experiment with the use of "phased array antennas" for focused sending and receiving, test the focusing and receiving performance of microwaves with different phases, and gather related scientific data. These experiments are crucial for both space power stations and microwave weapons. Below is a bird's-eye view of the experimental base in Bishan, Chongqing, China.